Like it or not, there is something about the word ‘whistleblower’ that makes me slightly uneasy. It takes me straight back to schooldays, to casual bullying and the threats of what would happen if I ratted or snitched on my mates. Even though I took those warnings to heart (‘what goes on in the chemistry cupboard, stays in the chemistry cupboard!’) the thing I feel most uneasy about is that I didn’t have the courage to stand up to them, to go boldly up to the teacher in front of the class and dob them in it: god knows, they deserved it. Thankfully, whistleblowers are nowadays not always the subject of furtive threats, behind-the-hand comments and a lot worse besides: in some circles, at least, standing up to systemic abuse and malpractice is something to be supported and even celebrated.

Did you know, for example, that in England there is now a National Guardian for the NHS, Dr. Henrietta Hughes, whose responsibility it is to provide ‘leadership, training and advice for Freedom to Speak Up Guardians based in all NHS trusts’ (https://www.cqc.org.uk/national-guardians-office/content/national-guardians-office). Her aim, and the aim of the office which she heads up, is to ‘lead cultural change in the NHS so that speaking up becomes business as usual’. Disturbingly, of the 7,000 cases that were raised with ‘Freedom to Speak Up Guardians’ in her first year in office, 361 (more than five per cent) were from staff members who alleged that they had been targeted by their employers for the very act of whistleblowing.

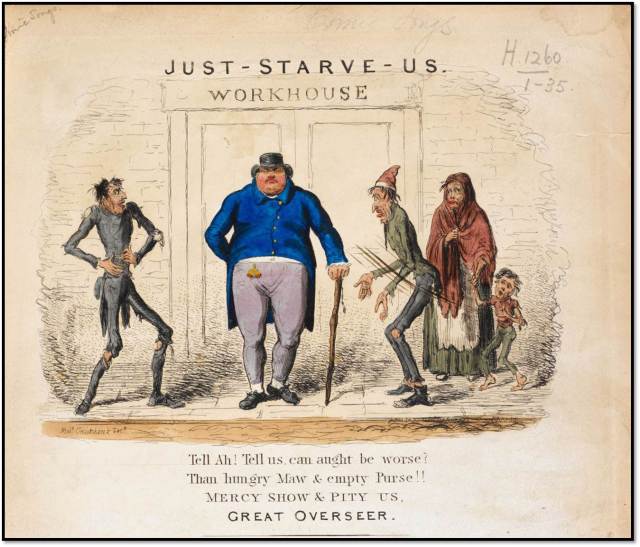

Here at ITOW, this puts us very much in mind of those who raised concerns about their own treatment, and that of many others around them, in nineteenth century workhouses. They, too, were whistleblowers of a sort, and they wrote in large numbers to the Commissioners for the Poor Law at Whitehall to complain of everything from the state of the food and the punitive work regime, to personal assaults by staff members and much worse besides. Many letters came from paupers who sought only personal redress, but there were those who took it on themselves to speak for the majority, directly challenging the authority of those who meted out poor treatment such as workhouse masters, medical officers, matrons and schoolmasters. At the extreme end of the spectrum was a small group of paupers who dedicated their entire lives (or, at least, that part of it they spent in the workhouse) to bettering the condition of their fellow paupers, and who not only blew the lid on poor treatment in workhouses but pointed the finger at the Boards of Guardians who were supposed to oversee them.

Thomas Gould was one such crusader. Formerly a businessman, like many others at the time he found himself destitute and unable to fend for himself in old age. At 72, he had already been in the Poplar workhouse for two years when he first wrote to the Commissioners in 1853 to complain of the ‘unnecessary harshness and tyranny’ that was ‘exercised over the quiet orderly aged and afflicted poor’ (MH12/7683). His list of grievances was long, from the oakum picking that the elderly and sick poor were forced to undertake (‘being from 6.a.m. to 6.p.m.’), to the short measures and poor food they endured at mealtimes. He accused the workhouse master of bullying and peculation, and of using workhouse provisions to clothe and fatten his own large family. Overall, Gould complained of a ‘want of system…and a want of classification,’ so that ‘all are huddled together. The young and the old the blind the lame and diseased’.

By the time of his third letter, in 1855, he complained of being ‘perpetually annoyed and insulted by the master and matron[,] by the Guardians and I may say by many of the inmates’ who sought to curry favour with them, for speaking out (MH12/7684). But he was not a man to be deterred. Despite a campaign of persecution against him, which included being taken before the magistrates for petty (and imaginary) offences and being deprived of the liberty to occasionally leave the workhouse, something routinely allowed to all other elderly inmates, Gould wrote a further eight letters over the next six years. In total, he wrote over 11,000 words of detailed, specific complaint. He named names, and listed many instances of embezzlement, cruelty (to himself and others), sexual misconduct and sundry breaches of the rules.

It is hard to know whether Gould’s tireless campaign really changed things for the better for the paupers of Poplar. The Poor Law Board always responded to his letters, and at least two small-scale inquiries were instigated as a result of his persistence. He himself believed that he had brought about a three-month suspension and a substantial fine for the workhouse master; but he also admitted that ‘upon the return of the Master to his former position, matters then droped again into their former miss rule, and so have continued’. In the end, we can only admire the persistence of a man who had nothing much to gain from his role as self-appointed watchman, and, while he remained a pauper in the workhouse, very much to lose; a man whose only motive was to fulfil ‘a duty which we owe to the Laws of my country, to your Honourable Board, to the poor, and to myself’. May we all have the courage to be a bit more Thomas Gould.

Very thought provoking, not much changes.

LikeLike

Pingback: ‘It’s Not Fair’: Natural justice and the New Poor Law – In Their Own Write