This month, we have two special blogs tackling the often difficult subject of the abuse of paupers in the workhouse. Today, Dr Carol Beardmore discusses the physical and mental abuse of pauper children in the context of recent inquiries into historical abuse…

On the 31st of July this year, the Independent Inquiry for Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) published its report into historical abuse in residential and foster care homes across Nottinghamshire. All in all, 350 people gave evidence to the inquiry: the largest group in a single investigation that the IICSA has considered to date. It concluded that the abuse of children was widespread across the county during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. It also concluded that victims were consistently failed by successive Nottinghamshire councils and by its Police force. Professor Alexis Jay who chairs the inquiry stated: ‘For decades, children who were in the care of the Nottinghamshire councils suffered appalling sexual and physical abuse, inflicted by those who should have nurtured and protected them’. She argued that, despite decades of evidence and any number of reviews which highlighted the problems of abuse, the council failed to learn the lessons from, or act on, those problems. From the late 1970s to the present some 16 residential staff and 10 foster carers have been convicted of the sexual abuse of the children in their care in Nottinghamshire. The hearings held by IICSA examined three key areas of interest: Beechwood Children’s home in Mapperley; foster care across the county; and harmful sexual behaviour between children in care. Beechwood came under particular scrutiny. It had at various times been an approved school, an observation centre, a remand home and a community home. Its reputation as a place where criminal and troubled children lived continued long after this function had ceased. The standard of care was described as ‘appalling’, with children being dragged across the room by their hair, stripped naked to stop them leaving, and forced to fight each other. One former resident stated: ‘It was a big place…a horrible place…there was nothing in there that was soft or homely’. This investigation took place, of course, against the backdrop of similar inquiries into historic abuse in Rochdale and Lambeth.

It has been argued that, in fact, Nottinghamshire is little different to any other county in Britain, and that the c.1000 allegations which have been made by more than 400 individuals simply demonstrates the extent of the problem overall. One thing is for certain: for those of us working on ITOW, stories of the abuse of children across the age range are all too familiar. Child sexual abuse is often a difficult crime to pin down in the nineteenth century because of the deep historical context. For example, the age of consent was only raised to 16 (from 13) in 1885. So, while we undoubtedly see cases of young girls becoming pregnant or being potentially abused prior to this, they were frequently of age in legal terms, and thus no crime was deemed to have been committed and little was written about them.

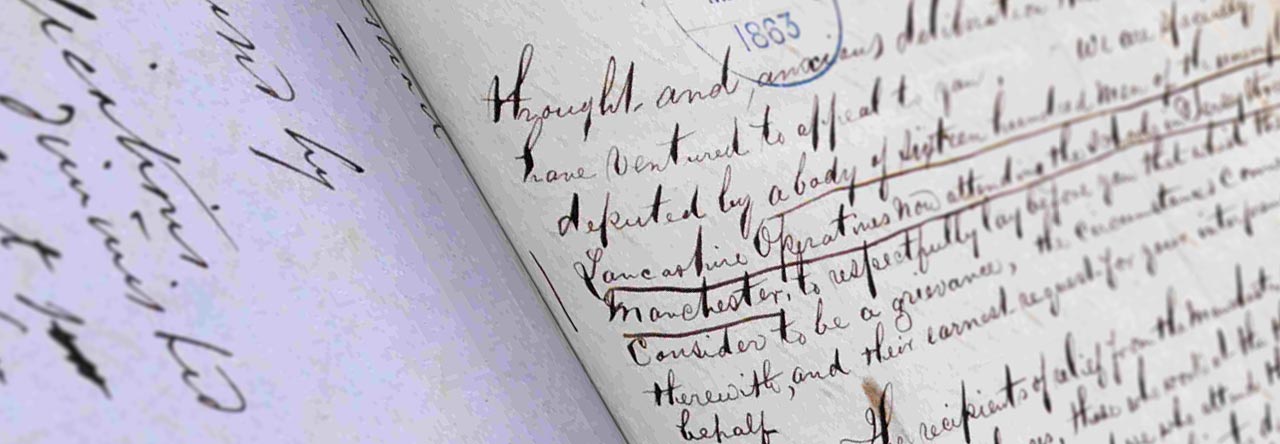

Unfortunately, cases of physical and mental abuse abound in MH12, however, and the voices of the children themselves are often heard (as in the Nottinghamshire inquiry) through witness statements or depositions. For a child in the workhouse, just as at institutions like Beechwood, coming forward took great courage – especially knowing that the perpetrator was likely to remain in post when the investigator’s left, to continue the cycle of abuse.

There were those who advocated on these abused children’s behalf, though. Often, complaints were made by adults, including other workhouse inmates. For example an inmate of the Newcastle-under-Lyme workhouse wrote to the Poor Law Commissioners in 1870 stating that ‘one of the boys here ran off last week to tell one of the guardians about the master treating him cruelly and got his hands cut to pieces with a cane when he got back’. At Newport, in May 1871, the central poor law authorities received a complaint to the effect that the workhouse school master had cruelly treated eight-year-old William Mahoney. At the inquiry which followed, Mahoney stated that:

Mr Bennett hit me in the face, knocked me down, and kicked me in the ribs, and then took me to the Greenhouse, and again beat me there. My nose bled much – He made me wash my nose in the water that came from the dung heap.

At the subsequent inquiry, other children lined up to give testimony on his behalf. John Palmer, who was 15, said ‘I saw Mr Bennett take hold of Mahoney & strike him with his fist … I was 10 yards off’. Mahoney’s thirteen year old sister on hearing of the attack on her brother absconded from the workhouse: this in itself was a considerable act of rebellion. Her treatment on her return, however, was indicative of the abusive nature in the workhouse as she was taken to the ‘bottom bed room’ and locked up by the Governess. Miss Hughes the Industrial Trainer then took her clothes and the child was kept in a state of nakedness for five days.

So far, the evidence from MH12 suggests that staff were rarely punished for their abusive treatment of children in the workhouse, with many simply being allowed to resign; but punishments did occur. Ella Gillespie, a nurse to the Hackney Union School, was accused of cruel and inhuman treatment towards the children in her care and prosecuted in 1894. Her catalogue of abuse verged on physical and mental torture and incorporated beatings, burning the children’s skin, withdrawal of food and water and the systematic disruption of the children’s sleep by forcing them to undertake nightly exercises. The evidence suggests that, much like Beechwood, this regime of abuse had been allowed to continue for many years. At the inquiry and trial that ensued, further incidents of her behaviour emerged which included banging heads against the walls, making children kneel on hot water pipes and whipping them while naked with stinging nettles.

Many of those who have followed the recent spate of harrowing IICSA inquiries have wondered just how the perpetrators were allowed to get away with it for so long. Though far from optimistic, the evidence from MH12 suggests that, in fact, such appalling treatment has been a systemic problem for Britain’s institutions for much much longer even than these investigations suggest. Highlighting the deep roots of historic child abuse, and calling out the failures of the constituted authorities to deal with it in the longue durée, may help us to create a climate of true reparation, and to look to a future where such things are simply not allowed to happen again.

Rutherford, for example, published an important first-person account of his experiences in the Poplar workhouse while he was still a pauper. It was titled Indoor Paupers, by ‘One of Them’, and was recently republished by Peter Higginbotham, of

Rutherford, for example, published an important first-person account of his experiences in the Poplar workhouse while he was still a pauper. It was titled Indoor Paupers, by ‘One of Them’, and was recently republished by Peter Higginbotham, of