We’re all familiar with it in some form or another: either George Sims’s original lament against the cold, hard world of Victorian welfare or Robert Weston and Bert Lee’s parody, where “dangerous Dan McGrew / was fighting to save the pudding / from a lady that’s known as Lou”. But whichever version of the popular song comes to mind there’s no doubt that Christmas in the workhouse is one of the most enduring sentimental tropes of Victorian popular culture, a potent mix of Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol, a Dickensian meat-feast of mawkishness and melodrama. But peel back the pathos for a moment and there is a surprising amount in Sims’s original lament that chimes with the real experience of workhouse paupers. From the festive decorations, to the seasonal (and exceptional) fare, and even the image of local dignitaries, including Guardians, serving at table, the scene could have been taken from real life, as attested by the Bradford Observer in 1848:

The various rooms in the workhouse were decorated with sprigs of laurel and holly, which gave the interior quite a cheerful appearance…Dinner was placed on the tables at two o’clock, when grace was sung. The dinner was served up in a manner which reflected great credit on the master and matron. Some 100lbs of roast beef, of first rate quality, had been provided, with potatoes, plenty of excellent plum pudding, and a barrel of good ale. The inmates appeared delighted, as well they might, with this unusual fare, and ample justice they did it. The Rev. Dr. Burnet, Mr. C. Rhodes, Mr. Wagstaff, Mr. Tetley, and other gentlemen were present to witness the interesting scene, and to wait upon the inmates.

Yet the real point of Sims’s lament was, of course, to show the underlying harshness of the New Poor Law and the lurid condescension of the workhouse feast. His hero is an elderly man who refuses to eat “the food of villains / whose hands are foul and red” because, as we soon discover, his wife died exactly 12 months prior to the feast. She was, he tells us, “starved in a filthy den” because the relieving officer refused to give him food, only offering them the refuge of the workhouse. This his wife refused, saying “Bide the Christmas here, John / we’ve never had one apart / I think I can bear the hunger / the other would break my heart”. Thereafter, she slipped away and died of hunger, steadfastly refusing to be parted from her husband by the workhouse rules. Here, too, we find plenty of evidence to support the darker side of Sims’s vision.

In January 1844, for example, John Houghton, Surgeon, wrote that he had visited Mary Ducie in Dudley Union. She was, he said, “in a very low and debilitated state lying on a few rags on…a small bedstead and covered with a few ragged clothes”. He contacted the relieving officer who, having initially allowed a few provisions, thereafter refused anything for her, even on application from Houghton. He then wrote that “on the 25th I asked her mother why she did not drink some milk as I ordered her. She said she had not the means of buying any. On Xmas day her husband said they should have had nothing to eat had not the neighbours given them some potatoes and a little bit of beef”. We don’t know whether Ducie died as a result of what the doctor called “want”, but the last time he saw her he described her as being in a “hopeless state” (MH12/13959).

John Tarby of Ditchampton offers us an another broad parallel with Sims’s account. In 1842, he was:

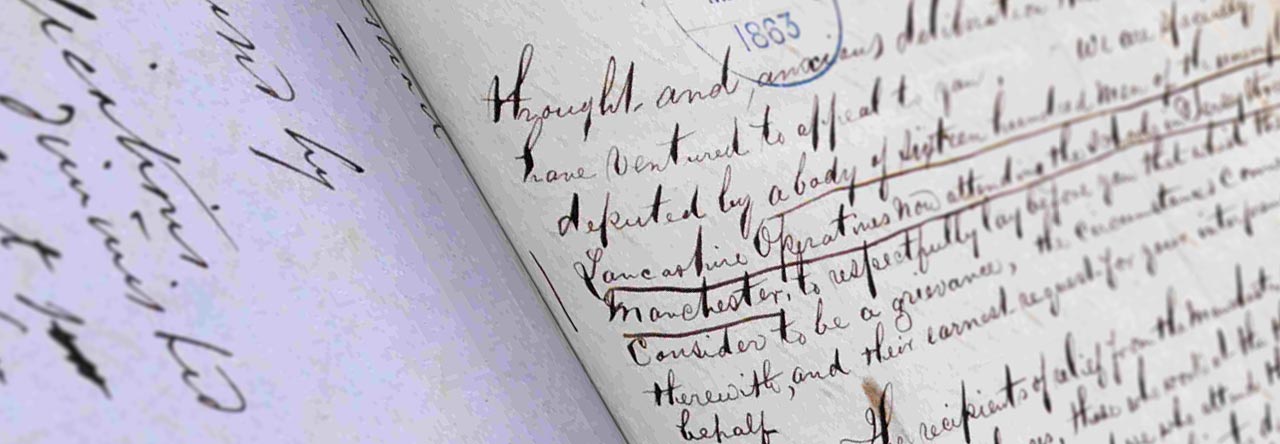

in my 70th year and have for upwards of 50 years contributed to the necessities of the the Poor – “The Beggar which I am now myself” – and to all other claims of Church and State, and the reply was conveyed by a direct refusal accompanied with an order to go into the House. That such was never contemplated by the Poor Law Amendment Act needs no comment and I therefore call on You in your Official Capacity to pervert this order – That such may not be a precedent in this Neighbourhood and that you may timely interfere is my prayer (MH12/13892).

Tarby was wrong, of course; there never was any stipulation that the elderly must be relieved outside the workhouse, although it was a common misconception among the poor that this was the case.

In many ways, it seems that Sims’s doggerel was a surprisingly accurate account of the cruelties of the poor law at Christmas. Yet, as is so often the case, things are not quite as straightforward as they first appear. For one thing, Sims was writing in the 1870s when the pressure of public opinion had forced many boards of guardians to treat the elderly poor with much more consideration. The vast majority were, in fact, relieved in their own homes, and workhouses increasingly provided shared accommodation so that those who came in as aged couples could continue to live together. For another, Mary Ducie’s case forces us to look again at the issue of institutional care for the sick and elderly more generally. Ducie’s case was a desperate one, as the surgeon made clear; she and her family had nothing but rags, they lived in destitution and had no way of keeping life and soul together. In this, they provide a direct parallel with Sims’s bereaved hero. Yet in cases like this it is quite possible to view the workhouse as a refuge in times of extremis, as many Victorians certainly did. No matter how unhomely its welcome, it guaranteed warmth, lodging and sufficient food; and, for those who needed it, it also guaranteed the services of a medical officer and, increasingly by the 1870s and 80s, the attention of professional nursing and care staff.

Which aspect of “Christmas Day in the Workhouse” we choose to focus on depends on the lens through which we view it, of course. But in the spirit of Dickens’ most heartwarming denouements – of which we will, no doubt, be served a double helping over the next few days – let us indulge ourselves on Christmas eve. Take yourself back to the Bradford workhouse in 1848; smell the cinnamon and pipe-smoke and hear the hearty cheers and contented murmurings of old and young alike. God bless us, everyone, from Tiny Tim and the ITOW project staff!

After all had eaten to their heart’s content, grace was again sung…Apples and oranges were then distributed among the children, a supply of tobacco was given to those who smoked, and a modicum of snuff to the snuff takers, while those who preferred it received 3d. in money instead. At five o’clock the inmates were again assembled, when spiced cake and cheese were served out, the women having tea and the men a pint of good ale as an accompaniment, and afterwards a glass of punch. ‘Health and long life to the Mayor’ was drunk with a sincerity and warmth of feeling rarely to be met with at a civic feast.

- A special festive thank you goes out to all our wonderful volunteers, whose time and dedication over the past two years has made the whole thing possible. We raise a glass of something mulled to you at Christmas!